|

本帖*后由 Stone654 于 2016-11-3 14:13 编辑 Tommy Emmanuel:万众瞩目 Adam Perlmutter,翻译Stone654

Tommy Emmanuel 正在弹奏他心爱的Maton原声吉他签名系列,这把吉他被他昵称为“黄老鼠”。图为一场2015年6月11日在纳什维尔的Cannery舞厅举办的向Jerry Reed致敬的演出。摄影:Andy Ellis。 大多数原声吉他演奏者都会一点Travis Picking 的技巧,这种切分节奏的指弹技巧是由传奇乡村吉他演奏家Merle Travis发明的。但仅有少数人能够使用这个技巧给乐曲注入活力,Chet Atkins就是其中一位,还有Tommy Emmanuel,一位来自澳大利亚的吉他大师,为被Chet Atkins冠以CGP头衔的五位演奏家之一。 Emmanuel现年60岁,他从6岁便开始职业生涯。在父亲的引领下,他和兄弟们开始在大篷车上公演以及跟随业余乐队巡演。后来Emmanuel成为了澳洲顶尖的吉他手,他的电吉他作品被收录于Air Supply和Men at Work这两个澳洲摇滚乐队的专辑中。 但Emmanuel*喜欢的是原声吉他的指弹演奏,近年来他推出了大量融合乡村、民谣、流行和爵士风格的专辑,均用一种耐人寻味,令人敬佩的方法演奏。没有什么比Emmanuel那像乐队一样的独奏更令人印象深刻的了。时隔15年,Emmanuel的新专辑It’s Never Too Late 绝对会让你大饱耳福。 在澳洲巡演时,Emmanuel通过Skype电话向我们讲述了他的音乐生涯,包括他与Chet Atkins的渊源。出于对吉他的全身心投入,他还用他的Maton吉他为我们演奏了一些作品的细节。 Q1:你的演奏风格是如此的多变,是什么让你开始演奏吉他的呢? A1:因为我母亲弹吉他,所以我自然也想弹。他在我四岁生日的时候买了一把吉他给我。我的兄弟姐妹也在相似的年纪开始演奏乐器,没多久我们就组建了一个乐队。影响我的第一个音乐风格是乡村音乐,我家里经常放Hank Williams, Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Snow和Jim Reeves等人的音乐。通过广播我接触了Chet Atkins,他是我年轻时*大的动力,他颠覆了我对音乐的认识。 “在我入门时,没有人能向我解释Jerry Reed和Chet Atkins的演奏是如何做到的,我只能靠自己去琢磨。” 之后我又接触了Les Paul, Merle Travis, Duane Eddy,当然还有Buck Owens和Merle Haggard。他们的专辑我都听,并尽我所能地去模仿诸如James Burton 和 Ray Nichols这些演奏家。在我年轻时,我主要听Don McLean, Gordon Lightfoot, Carole King, Neil Diamond和其他一些歌曲作家的作品。我沉迷于从歌曲中汲取营养并成为一名作曲者。之后我又接触了爵士乐、古典乐,以及R&B,各种音乐风格我都喜欢。 Q2:和我们聊一聊你听的音乐吧。 A2:对我的影响*初主要来自于Hank Williams和Jimmie Hammer,他们的歌我都学习过。Merle Travis 的Nine Pound Hammer和Doc Watson的Deep River Blues对我的影响也很大。我在70年代听了很多Tony Rice的东西,随后当然还有Larry Carlton以及Lee Ritenour等人的作品。我把他们的唱片买回家,尽我所能地从中学习。和别人一样,我也听爵士吉他演奏家Julian Bream和Andre´s Segovia的作品。Paco de Lucia对我的影响也非常大,他也许是我见过的*棒的吉他演奏家。 Q3:你在6岁时开始了音乐生涯,那是怎样一番景象? A3:乐趣很多,作为一个小孩子,你不会注意到一些艰难的东西,但我的父母肯定懂得拖着六个孩子全国演出混饭吃的艰辛。我母亲经常像变魔术一样就把吃的变出来了,但多我们来说这一切还是很欢乐的。我们喜欢演奏音乐,在路上我们结识了很多同龄人,并和他们一起做游戏钓鱼。 Q4:童年经历对你有什么影响? A4:毋庸置疑,这是我音乐生涯的一个良好开端。我学会了无论你多不开心,你都要站在台上演出,不能懈怠。现在当然好多了,我现在的生活方式曾经是那时的梦想:环游世界,在堂皇的礼厅演出。我一直怀有这种梦想,现在终于实现了。我仍然近乎疯狂地工作,这让生活充实并富有挑战,让我对自己的事业保持热血沸腾。 Q5:在那个学习资料匮乏的年代,你是怎样学习发展出你那知名的演奏风格的? A5:在我入门时,没有人能像我解释Jerry Reed和Chet Atkins的演奏是如何做到的,我只能靠自己去琢磨。我在唱片上面堆硬币好让它的转速变慢,试图理解那些更为复杂的粤剧。当时是有一些教材的,比如《Chet Atkins手把手教你弹奏》以及《Jerry Reed Heavy Pickin’》,但是我不识谱,所以只能欣赏欣赏封面的照片了。我得靠我的耳朵一点一点地听出来他们在弹什么。 当我遇到脑子比我快的人时,我总是会向他们请教。我会问他们:“嘿,这段是怎么弹的?”然后他们就会示范给我看。我喜欢向大牛们请教,因为可以彻夜交流彼此的演奏技巧。

Chet Atkins是Emmanuel对位演奏技巧的主要启蒙者。“当我欣赏他演奏的时候,映入眼帘的是一双经验丰富久经练习的手。”Emmanuel在谈起他的导师时说。“那是你目睹过的*优美的事物之一,单单看着他双手的运动,就有一种欣赏Fred Astaire的舞蹈的感觉。” 摄影:Jamey Firnberg Q6:你有没有获得过很大启发的时候? A6:又一次一个年轻的澳大利亚PG读者向我展示了一本记载Jerry Reed歌曲的书,他给我演示了Mister Lucky这首歌的正确指法。它很复杂,我甚至一个和弦都搞不懂。贝斯声部就像这样(开始弹奏该曲下行的贝斯旋律),然后主旋律是独立进行的(开始同时弹奏贝斯和主旋律声部)。这令我十分难忘。 Q7:第一次遇见你的偶像 Chet Atkins是什么感觉? A7:那是1980年,我从悉尼的家里出发,踏上去纳什维尔的朝圣路。我给Chet的办公室打电话说我到城里了,他说:“过来吧,我现在见你。”于是我跳上车以*快的速度赶到了他的办公室,他边下楼边说:“你想弹会吉他吗?” 随即我进了屋并开始弹奏Me and Bobby McGee这首曲子,他观摩了一会也跟着弹了起来,直接以和声填补空白,然后弹了一段solo。好像我们曾经排练过一样,这一切是那么的天衣无缝,着实是很神奇的体验。当我欣赏他演奏的时候,映入眼帘的是一双经验丰富久经练习的手。”Emmanuel在谈起他的导师时说。“那是你目睹过的*优美的事物之一,单单看着他双手的运动,就有一种欣赏Fred Astaire的舞蹈的感觉。 Q8:1997年你实现了你的梦想,与Atkins一起出了一张专辑:The Day Finger Pickers Took Over the World。这次合作是怎样开始的? A8:95年我来到纳什维尔为CMA做一档节目,我在一个叫Ace of Clubs的地方也有两场演出。Chet在演出的第一晚出席并鼓励了我很多,同时确认了唱片公司会在第二天晚上过来。 “我尽我所能向Chet这样的前辈致敬,努力把这种演奏风格呈现给年轻一代的听众。” 事情的发展出人意料。在我回家一周后,Chet给我打电话说:“哥伦比亚唱片公司很喜欢你的作品,并且认为我们两个应该合作。你想过来录一张专辑吗?”回过神来之后,我立即开始作曲,并通过电话弹给Chet听。他对这些曲子都十分喜欢,于是他们全部被收录进了专辑中。能和Chet一起作曲演奏一直是我的梦想,我们甚至获得了格莱美奖的提名。 在那之后,我们决定正式合作并雇用了一位经纪人。我们日程一致,并计划一起去Leno和Letterman等演出露面。但不幸的是,Chet被诊断出有脑瘤,必须手术,这一切只能取消。Chet出院后,身体一天不如一天,我们的合作计划也被永远地画上了句号。 总而言之,我尽我所能向Chet这样的前辈致敬,努力把这种演奏风格呈现给年轻一代的听众。奇妙的是,世界各地都有年轻的指弹吉他爱好者,无论是中国、马来西亚、日本还是俄罗斯和波兰,全世界都有练习这种指弹风格的人。 Q9:其他风格的演奏对你一定很有冲击性。 A9:是的,现在的年轻一代演奏者着实会让你大吃一惊,他们的演奏超乎你的想象。这很大程度上归功于科技的进步。如果有人在演奏会把我的演奏录下来,当天晚上你就能在Youtube上看到,第二天早上又会有四个不同的版本。现在的技术就是这样的! Q10:如果在你年轻时便有这种科技,对你的音乐可能会产生怎样的影响呢? A10:我可能会更多地被Andy Mckee这样风格的演奏家影响,因为现在网络上这种风格的演奏很多。但我不能想象我演奏其他风格音乐的样子,因为我的风格和我本人是合一的。我弹奏的时候,音乐便成了我的标签。那是属于我自己的声音,我并不想摒弃它。学会这种风格花了我很长时间,所以我总是用这种风格进行演奏。否则,我的音乐就会听起来好像100个风格的杂烩一样。 我认为每个人都会在年轻的时候发展出个人的独特演奏风格,余下的日子则用来精炼它。你听的越多,能弹奏的素材也越多,很多时候突然之间就会有灵感乍现。我记得以前听Chet Atkins早期作品的时候,能明显听出Merle Travis和Django Reinhardt的影子。但当Chet弹奏他自己的风格时,那就是属于他的声音——风格独特并有标志性的lick。 你会发现所有的吉他手都有这样的先天特质。记得第一次给Jerry Reed弹吉他的时候,我弹了一些曲子,他说:“这些曲子你不是学来的,而是与生俱来的。”这种说法很有意思,因为有些时候你却是觉得那些旋律时自然而然的,像是曲子找上你,而不是你写出了曲子。好比你汲取了乐符的精华,然后从指尖释放一样。 Q11:It’s Never Too Late这张专辑听起来好像现场录制的一样。 A11:这些曲子不是集中写成的。我并没有专门划一段时间来作曲,因为过去的几年里我一直非常忙。拿第一首曲子来说,是在去年十二月我在波兰巡演的现场录制的。我的小女儿在今年一月出生了,这首曲子是写给她的。 很多曲子都是在履行期间写的,旅行是可以给你提供丰富灵感的一件事。我写了一首叫Traveling Clothes的曲子,它也被收录在这张专辑中。如果你像我一样经常旅行的话,你会知道自己穿什么样的衣服*舒服。我想,如果我的衣服能够告诉我它到过那里,那该是一番何等有趣的景象(开始弹奏Traveling Clothes 选段) 这首曲子旋律多变,但基本上贴近我喜爱的Alison Krauss和Union Station的曲风。我一直在尝试谱写那种类似歌唱的旋律,当一个曲子不以吉他为中心时,它听起来会与其他人的纯器乐演奏不同。我经常写一些歌唱性强的乐曲。

Emmanuel 4岁开始弹吉他,6岁就以一个音乐人的身份活跃在舞台上。他的吉他是Maton的定制款,由澳洲的本土木材制造。 摄影:Jamey Firnberg Q12:你在The Bug之类的新曲子中应用Travis技巧使曲子富有神秘色彩。 A12:很高兴你能问这个问题,这个曲子是为我的妻子而做的,The Bug是她的昵称。她很守旧,这一点十分迷人,也解释了为什么这首曲子带有怀旧色彩。我尝试写一些能反映生活阅历的曲子,正如我的妻子一半。我认为这个曲子永远不会结束,因为它没有稳定的结尾段。(开始弹奏The Bug主旋律,见谱例1)在这些和弦之上我又发现了这个。(开始弹奏主旋律的伴奏,见谱例2) Q13:这首曲子的旋律非常优美,你是怎样写出如此复杂的和声的呢? A13:我并不认为它那么复杂,你听过Lenny Breau的曲子吗?(笑声)那才叫复杂!我只是写一些听起来感觉很棒的东西,而且和你所想象的吉他演奏家有些不同,我一直在寻找与众不同的和声弹奏方法。比如我在给Close to You(Burt Bacharach的曲子)在编曲的时候,发现了一些不同寻常的东西。(开始弹奏改编版本的Close to You) 我*希望的是带给听众惊喜,为他们演奏悦耳的音乐,所以我要让乐音不平稳且有特点。如果一段旋律过于美好,那么听一会之后便会显得甜腻,你要保持音乐的新鲜感。 “如果有人在演奏会把我的演奏录下来,当天晚上你就能在Youtube上看到,第二天早上又会有四个不同的版本。” 有一首老歌,可能比你的年纪都大,我在几年前把它录进了专辑。它叫Secret Love,原作者是Doris Day。我找到了一个用自然泛音弹奏旋律的方法,(开始弹奏乐曲的A段)在过渡段是这样的(开始弹奏有紧张和声和水波泛音的乐段=)。找到这些和弦费了一番功夫,但我知道它们是存在的。 Q14:你是怎样找到这些和弦的? A14:我先写出旋律,再慢慢摸索出指型。我必须通过练习才能让旋律流动起来,并保持伴奏同样顺畅。我想象自己在歌唱,保持旋律进行的同时加入不稳定和弦带来惊喜。 Q15:谈到Lenny Breau,你真的很喜欢使用水波泛音这一技巧。 A15:我*早在Chet Atkins那里听到了这种声音,但Lenny把它变得十分完善。我确实经常使用这一技巧,听听这个。(用水波泛音弹了一段色彩丰富的旋律)我寻求那种音乐上和谐而且听起来吸引人的和弦。Chet在他76年的专辑Chet Atkins Goes to the Movies中弹奏了Somewhere Over the Rainbow的一个版本。在曲子过门处,Chet随着贝斯手的旋律弹奏了那些美妙的泛音。 我在年轻时学会了这个技巧,这么多年来一直在完善它。现在我仍然在创新,寻找新指型和新声音,但技巧是一样的。它是泛音和按弦音结合的产物,这两者共同构成了一种类似竖琴的声音。 Q16:你在录专辑时使用的是什么吉他? A16:基本都是用我的Maton定制款:两把签名款的EBG 808 TE。他们在墨尔本制造,均使用澳洲北部的本土枫木。它和桃花心有很多共同点,比美国枫木声音更浑厚。多数音轨都是用这两把吉他录制的,在一些曲子中我会用一把Larrivee,那是Jean Larrivee很久以前给我的。我不知道它的型号,但它是缺角设计,琴颈与琴体连接处在12品的位置。面板采用熊爪纹云杉,背侧用玫瑰木,像小钢炮一样是个传奇。 Q17:专辑里的吉他声听起来很自然,你是怎么录制的? A17:我不插电,只是把一支50年代的老Neumann话筒放在吉他前面合适的位置。总的来说,我一般不在录音上花太多的时间。事实上,我希望自己有更多的时间来录音。多数情况下我先把歌写出来,演出它们确保一切合适,然后进录音棚花一两天时间把所有事情都搞定。我假装面对观众进行演奏;戴上耳机,坐在麦克风前,录音棚变成了我的天地。我十分享受这个过程,它可以让我知道自己弹奏的细节,从而带出*好的演奏状态。 Q18:回头谈谈专辑的第一首曲子,你给你的小女儿弹过吗? A18:当然,我喜欢给Rachel弹奏。她也很喜欢音乐,并且已经知道这首曲子是写给她的了。当她听到时,表情会变成这样。这真的是生活中*美好的事。 原文: Tommy Emmanuel: In the Zone Adam Perlmutter August 27, 2015 Most acoustic guitarists can do a little Travis picking—the syncopated fingerstyle approach pioneered by the legendary country guitarist Merle Travis—but few are inventive enough to use this technique as the foundation for new work. Chet Atkins was one of these players, as is Tommy Emmanuel, the Australian virtuoso and one of only five guitarists Atkins honored with his “Certified Guitar Player” award. Now 60, Emmanuel has been a professional musician since the age of 6, when he and his siblings, under the direction of their father, began living out of a station wagon and playing in informal touring bands. Later Emmanuel emerged as a top-shelf session player in his native country. His electric-guitar work can be heard on albums by such Aussie rock groups as Air Supply and Men at Work. But Emmanuel’s first love was fingerstyle acoustic and in recent years he’s developed a body of work that blends country, folk, pop, and jazz in the most tasteful—and often awe-inspiring—ways. In no situation is Emmanuel more impressive than when playing solo as a virtual one-man band. And so it’s a real treat that Emmanuel’s latest album, It’s Never Too Late, is his first new record of solo pieces in 15 years. Speaking via Skype while kicking off a tour in Australia, Emmanuel examined his musical life for us, including his deep connection to Atkins. And, being fiendishly devoted to the guitar, he couldn’t help but pick up one of his Matons to demonstrate some of the inner workings of his music. There’s such a wide roster of influences apparent in your playing. What first inspired you to take up guitar? I started playing because my mother was playing music and I wanted to as well. So she bought me a little guitar for my 4th birthday and that got me started. My brothers and sisters took up instruments at the same time and before long we were a band. My first musical influences were country: Hank Williams, Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Snow, Jim Reeves—that’s what played in my house. I heard Chet Atkins on the radio. He was my biggest inspiration when I was young, and he changed the way we all listen to music. “When I started, there was nobody around who could explain what Jerry Reed and Chet Atkins were playing, so I had to figure it all out by ear.” Then there were Les Paul, Merle Travis, Duane Eddy, and of course also Buck Owens and Merle Haggard. I listened to all their records, and I learned as much as I could from players like James Burton and Roy Nichols. During my teens, I listened mostly to Don McLean, Gordon Lightfoot, Carole King, Neil Diamond, and other singer-songwriters. I just kept an ear out for all the good songs. I was really interested in what I could learn from the songs and how I could become a songwriter myself. Later on I discovered jazz, classical, and R&B. I like all kinds of music and I always have. Tell us about some of those good songs. Hank Williams and Jimmie Rodgers were my first big influences—I learned all their songs. Merle Travis with “Nine Pound Hammer” and Doc Watson with “Deep River Blues” were big as well. I listened to a lot of Tony Rice’s stuff back in the ’70s. And, of course, along the way came Larry Carlton and Lee Ritenour and people like that. I bought all their albums and tried to steal as much as I could. Like everyone else, I checked out jazz guitarists like Wes Montgomery and Django Reinhardt. I got into classical for a while and listened to Julian Bream and Andrés Segovia, and also Paco de Lucía, who were such an inspiration to me, and to this day, probably the best guitar player I’ve ever witnessed. You became a professional at age 6. What was that like? It was a lot of fun because being a kid you didn’t notice all the hardships so much. I’m sure my parents did, dragging six kids around the country and trying to make a living. A lot of times I’m sure my mother had to perform a miracle to pull a meal out of the air. But for us it was fun—we enjoyed playing music and we met a lot of kids our age along the way, played games and went fishing, that kind of stuff. What have you taken from those years? It was a good start to my career, that’s for sure. I learned how to work hard and get out there and play, no matter how I was feeling. And things are a lot better now obviously. I’m actually living the dream I had back then when I’d fantasize about touring the world, playing in beautiful halls. I kept my dream alive and eventually got there. I’m still working like crazy at it, but it’s extremely fulfilling and challenging for me. It keeps me pumped about what I’m doing. Given that guitar instruction wasn’t nearly as accessible in your formative years as it is now, how did you learn to play in your signature contrapuntal style? When I started, there was nobody around who could explain what Jerry Reed and Chet Atkins were playing, so I had to figure it all out by ear. I’d get the record, stack coins on it to slow it down, and try to work out some of the more complex parts. There were some books—Chet Atkins Note-for-Note and Jerry Reed Heavy Neckin’—but I couldn’t read the music notation, so I looked at the photos and that’s about it. I had to work it out myself. Every now and again I’d run into someone who had figured out more than me and I’d say, “How does that go?” and they’d show me. I’d always love it when I’d run into guys who were much more advanced because we’d stay up all night showing each other stuff. Did you have any light-bulb moments in your musical development? One time there was a young Australian guy who was a good reader. He had the book of Jerry Reed songs and he showed me the right fingering for a song called “Mister Lucky.” It was complex, and I just couldn’t figure out half the chords. It was one of those things where the bass went like this [plays the piece’s descending bass line] while the melody moved independently. [Plays the bass line and the melody simultaneously.] Those were the kind of moments I’ll never forget. What was it like to encounter Chet Atkins, your hero, for the first time? It was 1980 and I made the pilgrimage to Nashville from Sydney, where I was living in those days. I called Chet in his office and told him I was in town, and he said, “Well, come down, I’ll see you right now.” So I jumped in the car and raced down to his office. As he came down the stairs, he said, “Do you wanna pick a little?” So we went into a room, and I started playing “Me and Bobby McGee.” He watched me for a while and then just jumped in. He went straight to harmonies and little fills, and then took a solo. It was just like we’d rehearsed it—it was so perfect against what I was doing. That was an amazing feeling. When I watched him play, I saw all the experience and practice in his hands. It was one of the most beautiful things you’ve ever seen—just watching his hands move around, like watching Fred Astaire dance. Beautiful. In 1997 you realized a dream when you released an album with Atkins—The Day Finger Pickers Took Over the World. How did that collaboration come about? In ’95 I came to Nashville to do a showcase for the CMA week, and I also played two shows at a place called the Ace of Clubs. Chet came down the first night to see me play and he was really encouraging and excited about the whole thing, and he made sure the record company came down the next night. “I’m out here doing my best to honor Chet and others who came before me, and to keep this style of playing alive by bringing it to the younger generation.” They were pretty knocked out with how everything went, and about a week later when I was back home, Chet called and said, “Well these Columbia people really like what you do and they think we should work together. Would you like to do an album?” After I picked myself up off the floor, I immediately started writing songs. I played them over the phone to Chet, and he liked them all, so they ended up on the album. I had the dream experience of writing and playing with Chet, and recording and producing the album. We even got nominated for a Grammy. After that, we decided to work together in a very serious way and hired a publicist. We got a schedule together, and we were about to go to Leno and Letterman and all those shows. But unfortunately we had to cancel everything because they found a tumor in Chet’s brain and he had to go have an operation. When he came out, his motor skills were diminishing by the day. And so sadly, that never had a chance to take off and come to fruition. Anyway, I’m out here doing my best to honor Chet and others who came before me, and to keep this style of playing alive by bringing it to the younger generation. It’s so fantastic that there are young players everywhere around the planet—China, Malaysia, Japan, Russia, Poland, you name it. All around the world there are young pickers just going for it. It must be wild for you to hear those players. Yeah, there are a lot of young players who would surprise the heck out of you—they’re a lot more advanced than you can ever imagine. A lot of this is because they’ve got their fingers on technology. If I play a song in a concert and someone films me, it’s on YouTube that night and there are four other versions by 6 a.m. That’s how it works these days! If this technology had been available when you started playing, how would it have affected your music? Maybe I’d be more influenced by somebody like Andy McKee, if I were a young person, because there’s a lot more of that style now on the Internet. But I can’t imagine playing any other way than I do because my music is me and I am it. When I play, it’s my signature. That’s my sound, my voice, and I don’t try to stray from it in any way. It took me a long time to develop that voice, so I just try to stick at it. Otherwise you end up sounding like a hybrid version of 100 people. We all develop a particular style at a young age, I think. But then it gets refined, the more information you take in and the more you put out. All of a sudden you’ve become a channel of ideas and flow. I remember when I first heard Chet Atkins’ early stuff, I could hear Merle Travis as much as I could hear Django Reinhardt. But when Chet played one of his own tunes, there was his sound. There was his distinctive style and his signature licks. You realize that all guitar players have these things in their DNA. I remember the first time I played for Jerry Reed. I did a couple of songs and he said, “You didn’t learn that—you were born with it.” It’s an interesting statement because somehow it does in fact feel like the music has always been there. It’s almost like it leapt on you, not that you discovered it—like it’s been in the air and you’ve just finally breathed it in and now it’s come out of your fingers. The compositions on It’s Never Too Late have a lived-in feel. I wrote the songs over a period of time. I didn’t really set time aside to write because I’ve been as busy as a one-armed fiddler in the last couple of years. The title track, for instance, I wrote last December when I was on tour in Poland because we were about to have a baby. My daughter Rachel was born in January of this year, and that’s her song. A lot of the other songs were written in my travels. Of course, traveling itself is such an inspiration for me. I wrote a song called “Traveling Clothes,” which is on the album. When you travel as much as I do you figure out the right kind of clothes for feeling comfortable. I also thought, what if my clothes could talk and tried to tell the story about where they’ve been? [Plays an excerpt from “Traveling Clothes.”] The song has a lot of movement. It’s pretty much written in the style of Alison Krauss & Union Station—that kind of big melodic sound I really love. I tried to find passages where I could play a vocal-harmony type of sound. When it’s not so guitar-oriented, that makes you sound different from other players. I often write an instrumental as if I’m going to sing the song. You’ve got an uncanny way of taking the Travis approach to new places, like on “The Bug.” I’m glad you mentioned that because the song’s about my wife—The Bug is her nickname. She’s old-fashioned, which is a real beautiful quality, and that’s why it’s in an old-timey style. I tried to write something that’s full of life, like she is. I call it the never-ending song because it never resolves. [Plays the main theme to “The Bug,” transcribed in Ex. 1.] And then to play over those chords I found this … [Plays a variation on the theme—see Ex. 2.] What a lovely progression. How did you develop such a sophisticated sense of harmony? I don’t think it’s that sophisticated—have you ever heard of Lenny Breau? [Laughs.] Now that’s sophistication! I just try to write things that please my ear. I’m always trying to look for ways of doing harmonies that are a little different from what you’d expect from a guitar player. Like for instance, when I did an arrangement of [the Burt Bacharach song] “Close to You,” I found sounds that are unusual. [Plays a chord-melody version of “Close to You” with extensive chord substitutions.] What I really want to do is surprise you, the listener, with things that tickle your ear, so I found a way of making things sound unexpected and unresolved. If everything sounds too sweet, then after a while, it all sounds boring. You’ve got to do things that keep the music interesting. “If I play a song in a concert and someone films me, it’s on YouTube that night and there are four other versions by 6 a.m.” There was an old song—it’s probably long before your time—I recorded on an album a couple of years ago. Called “Secret Love,” it was originally done by Doris Day. I found a way to play the melody in natural harmonics. [Plays the song’s A section.] And then when the bridge comes around I do this ... [Plays a passage with thorny harmonies and harp harmonics.] It took me a while to find those chords, but I knew they were there. How did you find them? I find where the melody is first, and then I just go looking for those shapes. I have to practice to make the melody flow well, while keeping the backing underneath and making it all fluid. I try to think of it like I’m singing, keeping the melody moving but at the same time offering those little musical surprises, which are the unresolved chord sounds. Speaking of Lenny Breau, you really use those harp harmonics to excellent effect. That’s a sound I first heard from Chet Atkins, and Lenny really perfected it. I use those sounds a lot—there’s this group here. [Plays a colorful progression using harp harmonics.] I just go looking for shapes that musically make sense and have an intriguing sound. Chet did a version of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” on his album Chet Atkins Goes to the Movies, from around ’76. On the intro, the bass guitar plays the melody while Chet plays those beautiful harmonics. I worked those out when I was young and just kept working on it. Every now and then I go looking for new stuff, new shapes and sounds. But it’s the same technique, a combination of harmonic notes and fretted notes as well, the two together creating that beautiful harp-like sound. What guitars did you play on the record? Mostly my custom Maton guitars, two signature-model EBG808TEs, which are made in Melbourne, Australia. They’re made from indigenous woods—maple from the northern part of Australia, which has a lot of the qualities of mahogany, actually, with a deeper sound than U.S. maple. I used those two guitars for most of the tracks, though on a couple of songs I played my Larrivée, which Jean Larrivée gave me a long time ago. It’s a cutaway with a neck that meets the body at the 12th fret, though I couldn’t tell you exactly what model it is. It’s got rosewood back and sides and a bear-claw spruce top. That guitar is a cannon—it’s a wonder. The guitars sound very natural on this album. How did you record them? I didn’t plug in or use any electronics. I just put one mic—an old Neumann from the ’50s— in front of the guitar, found a good spot, and there it stayed. In general, I don’t spend a lot of time recording—in fact, I wish I had more time for recording. A lot of times I write the songs, play them live to make sure everything is working, and then go into the studio for a day or two and pretty much get everything done. I try to play as if before an audience. To be playing guitar in front of a mic while wearing headphones—that’s the zone for me. I enjoy it so much and it really brings out the best in my playing when I can listen and examine what I’m doing, as I’m going. Getting back to the title track, have you played it for your new daughter? Yes—I love playing for Rachel and she loves music. She already knows her song. As soon as she hears it, she gets this look on her face. It’s the best thing in life, it really is. 附:Tommy Emmanuel的装备: Guitars Maton EBG808 “Yellow Mouse” Maton EBG808 “Orange Mouse” Custom Larrivée “The Boss” Amps and Effects AER Compact 60 AER Pocket Tools Colourizer Strings and Picks Martin SP Flexible Core (.012–.054) Jim Dunlop medium thumbpicks Kyser Quick-Change capos 谱例: 谱例一:

Tommy Emmanuel’s “The Bug,” which he thinks of as a never-ending song, pairs a looping jazz-inspired chord progression with Travis picking (Ex. 1). Palm-muting the bass notes helps give the piece a driving feel. Though Emmanuel frets the 6-string A notes with his thumb, alternatively you can play them on the open 5th string. For a real treat, be sure to hear Emmanuel grab his Maton to play this and the following two examples. 谱例二:

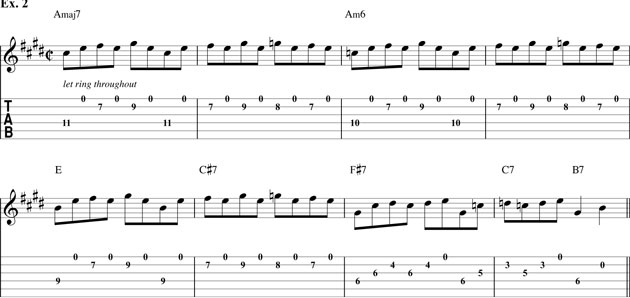

An intriguing variation on the main theme of “The Bug,” Ex. 2 is a neat picking pattern that includes an open-E common tone between the chords. Try plucking the 4th-string notes with your thumb and the rest with your other fingers, and let all the notes ring throughout. 谱例三:

Emmanuel is known for his masterly use of harp harmonics, a technique he borrowed from Chet Atkins and Lenny Breau. Like Atkins and Breau, Emmanuel pits the harmonics against fretted notes to create beautiful cascading effects. To play Ex. 3, keep each chord shape fretted for one bar, and for the harmonics, gently touch the string 12 frets above the fret-hand note (at the fret indicated in parentheses), while plucking the string with your thumb. Once you’ve got this figure down, see if you can extend the idea to some of your own favorite chord voicings. |